By Dershnee Devan

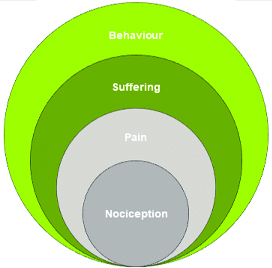

John Loeser proposed a model of pain that was far ahead of its time in 1980. At that time, the medical fraternity at large viewed pain from a biomedical perspective. It proposed that the experience of pain was covered by four nested circles that held the components of pain namely nociception, pain, suffering and pain behaviour (shown above).

This model has helped many clinicians understand the value of looking deeper than just the client’s physical presentation. Loeser framed this model as a biopsychosocial approach as it acknowledged a client’s suffering and validated their pain behaviour (Loeser, 2000).

It has indeed helped progress thinking of persistent pain as more than a sensory experience and helped provide a great foundation for the biopsychosocial approach to pain management. The biological and psychological spheres of the pain experience have been researched, investigated and used extensively in treatment. The social sphere or context on the other hand while acknowledged is not afforded the same level of attention.

Why is social context important?

It is important because we do not live in a vacuum, as human beings we thrive on connection. Our shared experience validates our own version of reality.

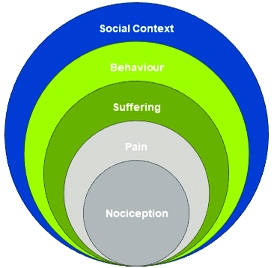

The social context provides the much needed validation, acknowledement and often reassurance from others when we experience disabling symptoms that occur with persistent pain. When an employer, loved one, friend or health care provider does not provide that validation or acknowledgement our pain experience is worsened. I would like to propose a more holistic model by adding another layer to the Loeser model – the social context displayed below.

When our reality does not match other’s perception of our reality i.e. our symptoms are not real because they do not believe it is as severe or disabling as we portray them. It results in more effort on our part to disprove their beliefs which affects our pain behaviours and eventually influences the level of pain experienced.

Validation, acknowledgement and reassurance that we have heard a client’s story, truly listened to their distress and believe that their pain is as bad as they say it is. These I believe are the keys to building a good therapeutic relationship, having better clinical outcomes and truly understanding their pain experience.

References

Loeser, D. J. (2000). Pain and Suffering. Clin J Pain, 16, S2-S6.